Summer is one of my favorite times of year. I love the sun, the long days and the blooms in my garden. But perhaps the reason I like it most is that there are no big holidays to get ready for. In the church calendar, we are in “ordinary time” and this long stretch from Pentecost to Advent is a time when we can focus on our “ordinary” days. I can ask, how do I spend my time when I don’t have the extra obligations of the busier times of year? How can I live with more joy and a balanced rhythm of work and play?

One way to do this is by “savoring.” We all know what it means to savor our food. It means appreciating the smells, colors and textures, lingering at each bite, and enjoying the taste. It had never occurred to me we could “savor” other experiences. Perhaps ordinary time is a time to savor the ways God has met me in the first part of the year. In my times of prayer or meeting with my spiritual director I can recall and savor the special moments from the last six months, like the time a friend was baptized or my trip to visit my older son. I feel more joy when I remember the sights and sounds of these events.

I am also learning to value silence. Most days I try to take a long walk in my neighborhood. It’s easy to fill that walk with noise—music or a podcast. Those are not necessarily bad things. But I’d like to experiment a bit with silent walking. I notice more of my surroundings when I am unplugged. I make space for creative thinking and maybe even prayer.

There is still work to be done in ordinary time. Sometimes it feels quite, well, ordinary. There is shopping, cooking, cleaning, paying bills, planning trips. We all have to do a lot of routine and often boring tasks. In my better moments, though, I remember the example of Brother Lawrence, the 17th century monk who found peace in washing dishes in the monastery kitchen. He was a believer that we can experience God not just in “spiritual” activities like church but in our everyday, menial tasks.

Many contemporary authors write about this idea of experiencing God in the ordinary. Tish Harrison Warren explores this concept in her lovely book “Liturgy of the Ordinary, Sacred Practices in Everyday Life.” She breaks down a typical day, from waking up and getting dressed to losing her keys and checking e-mail, and shows how each activity is not so different from the elements of a Sunday worship service. Waking up, for example, is like baptism and “learning to be beloved.” Losing keys is like confession (because she realizes how angry and frustrated she can get by such a small thing). I particularly like her “fighting with her husband.” She compares that to passing the peace and the “everyday work of shalom.”

All of the small, ordinary events of our lives can be sacramental, says Harrison Warren, meaning that God can meet us in the “earthy, material world where we dwell.” I hope to reread this book this summer and pay more attention to the rhythms of my daily life.

This summer, unlike most summers, my family has no big travel plans. Maybe that’s why I’m feeling like I can embrace this ordinary time even more fully. Perhaps this is the summer to appreciate where I live, where God has placed me. I’m eager to attend the outdoor theater production in a neighboring town and I look forward to exploring parts of the city I’ve never been to. I know there are projects at home too. We will be putting a new roof on our house sometime in the next few months, and I’m mindful it will require patience and a heart oriented to thankfulness. I also appreciate this summer as a pause before my son’s senior year of high school, a year that will be filled with a lot of busyness as he prepares college applications and graduation requirements.

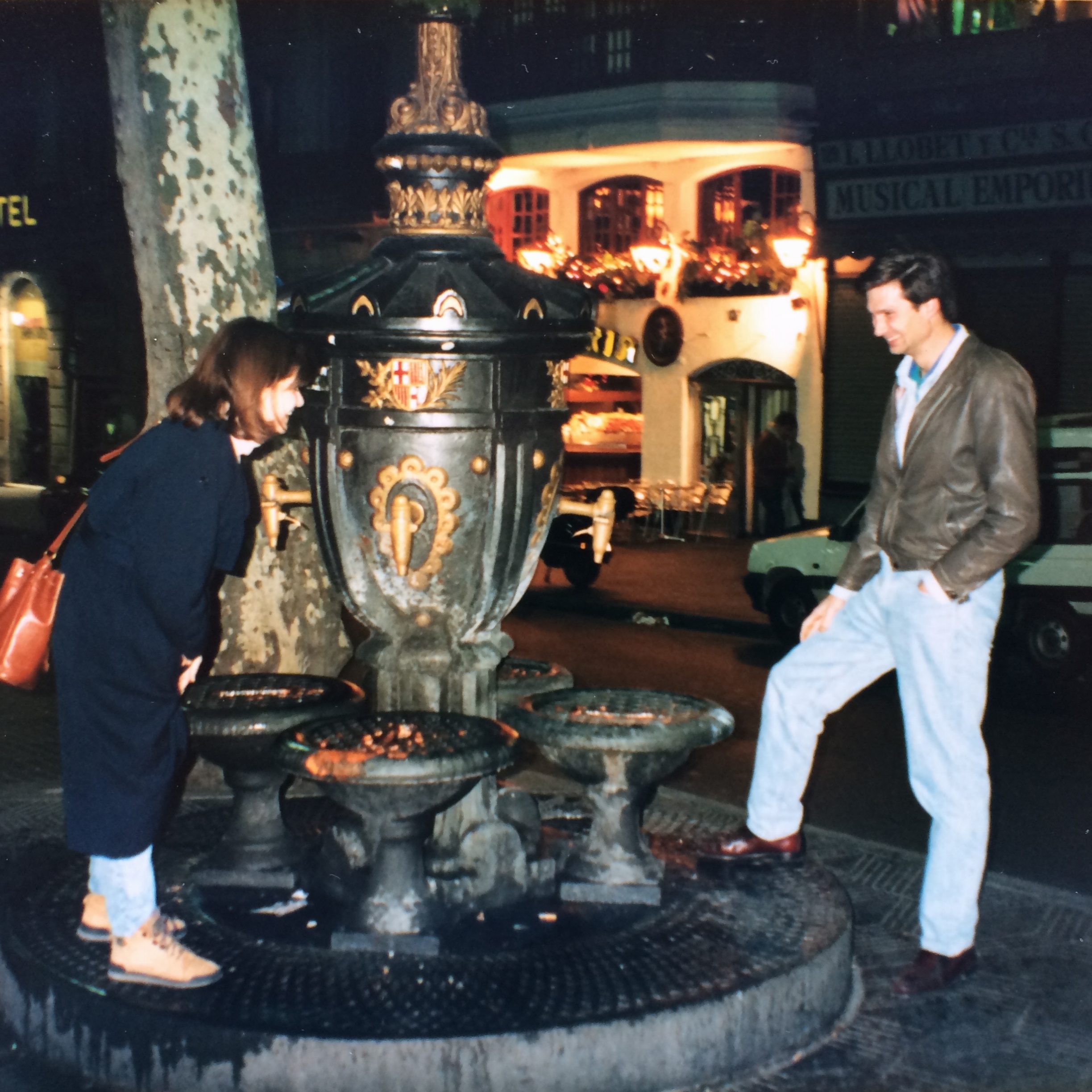

As I write this it is almost the summer solstice, the longest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere where I live. It’s a great time to practice savoring. In particular I remember past summers when I was traveling in some beautiful places. I especially remember several trips to Northern Spain, where, because of its geography, the sun didn’t set until nearly 10 pm. I’ll never forget the lively nighttime streets, the delicious tapas and paella, and our rosy cheeks from a day at the beach. I’d like to be back there again, but the memories are almost just as good.

What can you savor during this ordinary time? How can you build more silence into your days? And how can you be aware of the sacramental in the ordinary, everyday tasks of life? A friend of mine recently recounted how she had been gone for three weeks and when she returned a sunflower in her yard had grown about five feet! This reminded me that in this season of light and ordinariness amazing things are happening all around. This season, void of big holidays, can be the perfect time to notice the holy in the everyday and find reasons to orient ourselves toward joy and peace. We just might need more joy and peace in the busier times of year.

Do you have a favorite time of day? Maybe it’s looking forward to that first sip of coffee in the morning. Maybe it’s listening to your favorite song or podcast on the way home from work.

Do you have a favorite time of day? Maybe it’s looking forward to that first sip of coffee in the morning. Maybe it’s listening to your favorite song or podcast on the way home from work. “Sometimes the truth depends on a walk around the lake” – Wallace Stevens

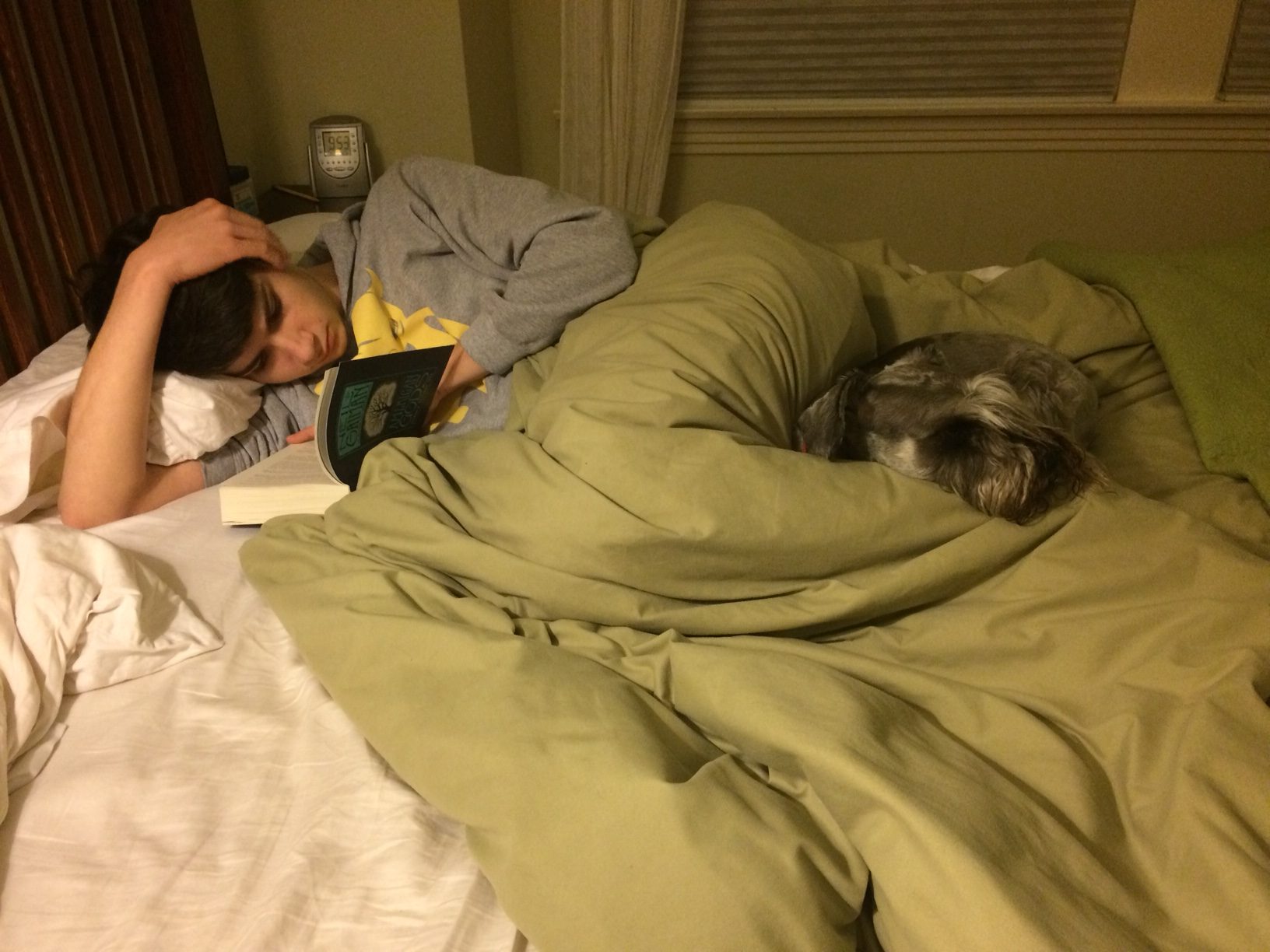

“Sometimes the truth depends on a walk around the lake” – Wallace Stevens My son and I surveyed the stacks of clean clothes on his bed. Did he have everything he needed for his second year in college? And what about his guitar propped against the wall? Should he bring that along too? We bantered back and forth about packing details and I tried to imagine what it was going to be like for my son to move into his first apartment off campus this year.

My son and I surveyed the stacks of clean clothes on his bed. Did he have everything he needed for his second year in college? And what about his guitar propped against the wall? Should he bring that along too? We bantered back and forth about packing details and I tried to imagine what it was going to be like for my son to move into his first apartment off campus this year.

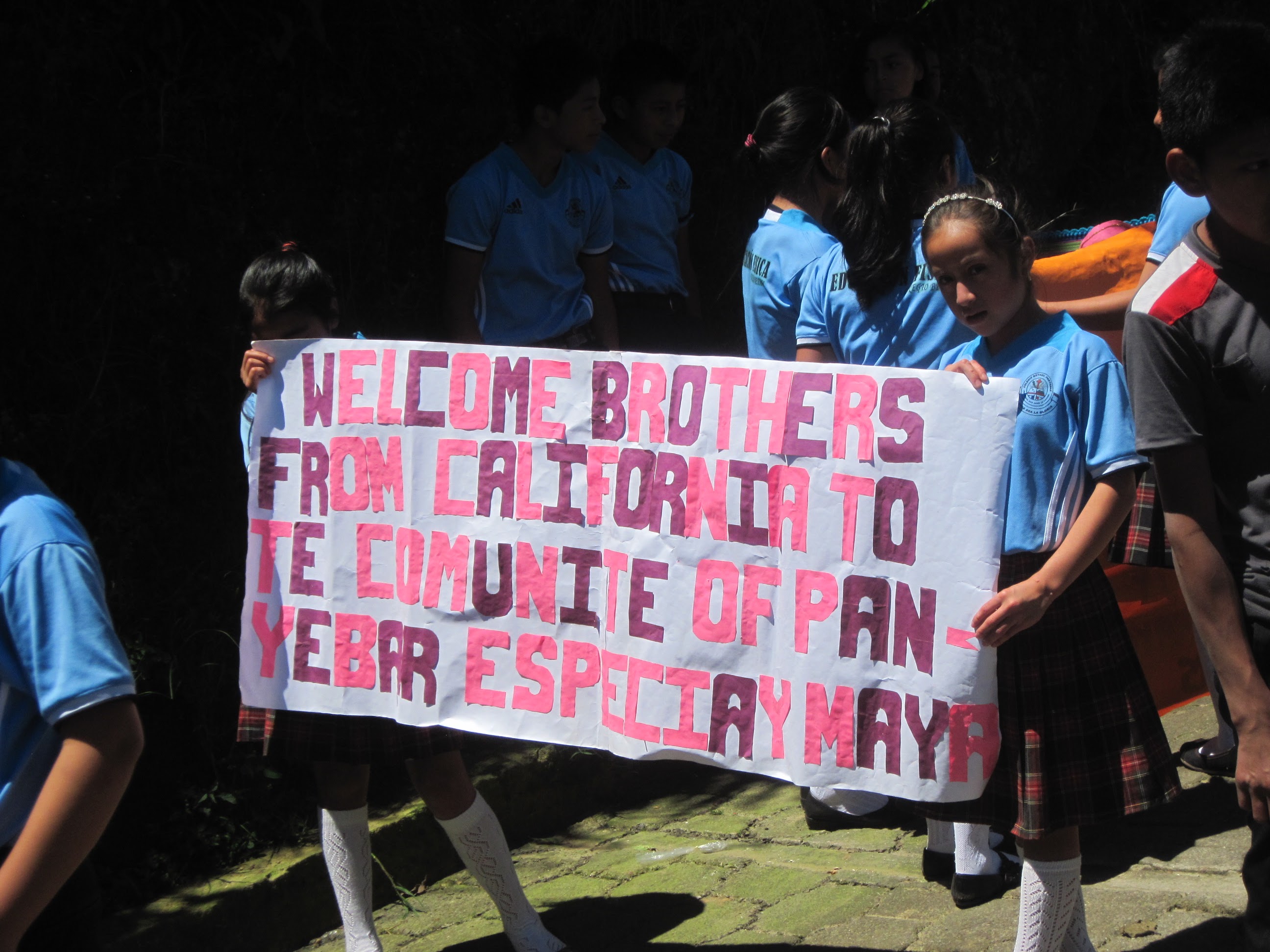

As I explained in my last post, spending a week in the little town of Panyebar, Guatemala recently was a little like a family reunion. Our “family” of Mayan Partners supporters, ages 7 to 50+, joined a group of Guatemalans of all ages, and the results were lovely and heart-warming. Like any family though, there are complex dynamics at work and some situations feel so fluid and unresolved you can only let go and let God (hopefully) direct.

As I explained in my last post, spending a week in the little town of Panyebar, Guatemala recently was a little like a family reunion. Our “family” of Mayan Partners supporters, ages 7 to 50+, joined a group of Guatemalans of all ages, and the results were lovely and heart-warming. Like any family though, there are complex dynamics at work and some situations feel so fluid and unresolved you can only let go and let God (hopefully) direct.

Another situation that left me somewhat confused happened with a former employee of the school, a woman named Flory. Flory had been a secretary at the school until a few years ago when our group and local leaders decided to implement a policy to eliminate nepotism, which had caused some problems. (Flory is the daughter-in-law of the head of the local committee that runs the school. Her husband Feric and some other teachers also had to leave the school because of the nepotism rule.) Our group reached out to Flory after she lost her job and asked her to make handicrafts for sale in the U.S. as a way to earn income. For two years, she and a group of other women made Christmas ornaments that we sold. We sent many e-mails back and forth to coordinate. Then, this year, I stopped hearing from Flory. My many e-mails went unanswered. What had happened?

Another situation that left me somewhat confused happened with a former employee of the school, a woman named Flory. Flory had been a secretary at the school until a few years ago when our group and local leaders decided to implement a policy to eliminate nepotism, which had caused some problems. (Flory is the daughter-in-law of the head of the local committee that runs the school. Her husband Feric and some other teachers also had to leave the school because of the nepotism rule.) Our group reached out to Flory after she lost her job and asked her to make handicrafts for sale in the U.S. as a way to earn income. For two years, she and a group of other women made Christmas ornaments that we sold. We sent many e-mails back and forth to coordinate. Then, this year, I stopped hearing from Flory. My many e-mails went unanswered. What had happened?