Sam Genirberg was a 17-year-old high school student when German troops invaded his home country, the Ukraine, in 1941. Little did he know that within a few months, the 12,000 Jews in his small town would be taken from the their homes and forced to live in a ghetto. Soon after they would be marched to pits outside of town and brutally murdered, part of the Nazi extermination of Jews.

Sam escaped that fate only because his mother begged him to flee a few days before the mass killing. She saw what was coming, even when most of her neighbors were in denial. They knew of the anti-Semitism of the Nazis, but they couldn’t believe innocent people would be killed.

Now, more than 70 years later, Sam still gets emotional as he talks about his mother. His voice wavers a little.

“It was very difficult to walk out of my house and leave my mother, knowing they would kill her. That feeling never left me. It’s still painful. Sometimes I think I shouldn’t have left,” Sam said.

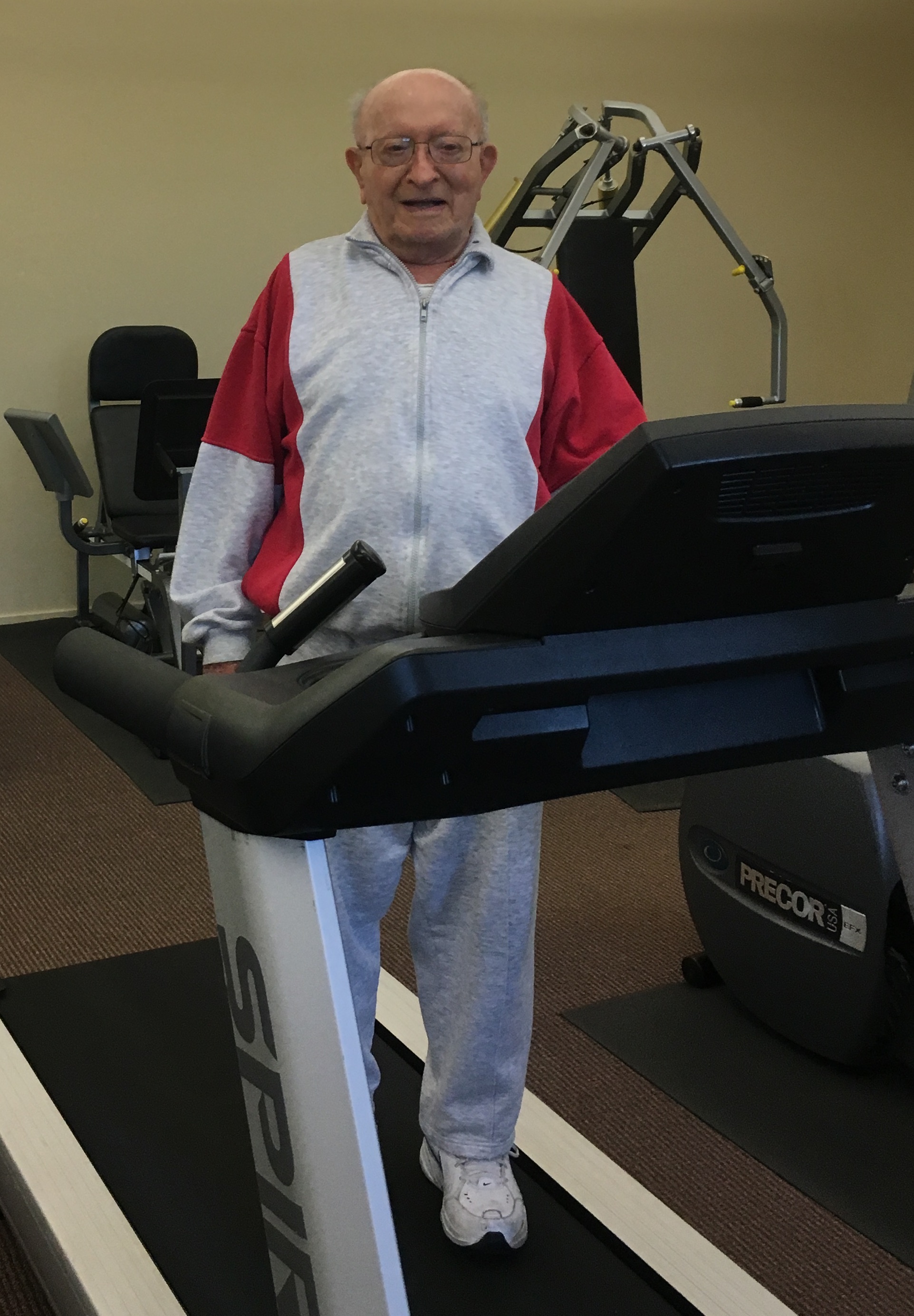

I met Sam several years ago at the Berkeley Country Club, where we are both members. For a few years he, my husband and my son worked out daily in the exercise room. My husband and son got busy with other activities and stopped working out, but Sam, still energetic at 94, continues his morning workouts five days a week.

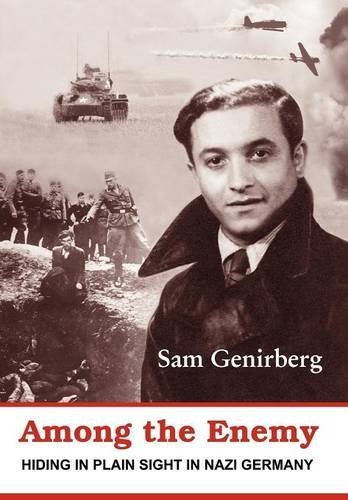

Sam is well-known at the club. He wrote a book detailing his three years surviving as a Jew in Nazi Germany. He self-published the book, “Among the Enemy” in 2012 and spoke at many schools and churches. These days, he doesn’t get asked to speak as much and was appreciative I asked to talk to him. He signed the title page of my book in capital letters, “NEVER AGAIN.”

Sam makes a point of telling me that in all the literature about the Holocaust, his story is unique—and he adds without irony—it may be the best. It is not set in a concentration camp. Instead, Sam worked in various factories, shops and farms in wartime Germany, all the while posing as a non-Jew. He was always one step away from being discovered and had to run away from work sites many times after co-workers began to suspect he was Jewish.

Sam makes a point of telling me that in all the literature about the Holocaust, his story is unique—and he adds without irony—it may be the best. It is not set in a concentration camp. Instead, Sam worked in various factories, shops and farms in wartime Germany, all the while posing as a non-Jew. He was always one step away from being discovered and had to run away from work sites many times after co-workers began to suspect he was Jewish.

It’s hard to believe it now, seeing Sam sitting comfortably in his spacious hillside El Cerrito home, but Sam survived incredible odds–with a combination of luck, talent and bravado. Before he escaped from his hometown, a sympathetic non-Jewish neighbor woman gave Sam her sister’s ID card and birth certificate. Sam changed the name on the documents from Anna Trag to Andrey Trag and adjusted the birthdate closer to his own. These papers would help him enter Germany with the thousands of other Soviet citizens like him who came to find work in the busy German factories. Because Sam spoke fluent German, which he had learned in school, he was treated more favorably by his employers. And since he did not look particularly Jewish, with his sandy blonde hair, he could pass more easily as a gentile.

“It took a lot of courage and audacity for an 18-year-old Jewish boy to survive the war in Germany after what the Germans had been doing. It was not an easy decision to make. I never heard anybody else going through those episodes in Germany like I did,” Sam said.

There were plenty of close calls. Sam’s first job was as an interpreter in a German factory. His boss wore an SS badge on his lapel and regularly beat the Soviet workers, whom he disliked because Germany was at war with the Soviet Union. But Sam’s real nemesis was the head interpreter, a man named Netzel.

When Sam met Netzel, he asked Sam for his full name and birthplace. Then he said quickly, “Are you a Jew?” Sam was shocked but realized he couldn’t show any fear or hesitation. He quickly and loudly responded that he was a full-blooded Ukranian and he would be happy to take the matter to the Ukranian National Committee. The interaction drew the attention of others and Netzel backed down.

But Netzel’s response was chilling: “Soon I will not have to take such precautions for the Jews of Europe are being liquidated quickly. In time there won’t be any of them left to be suspicious about. We all live for that day, don’t we?”

Netzel continued to be a thorn in Sam’s side, trying to get him to confess to being Jewish. One day, Sam and the other workers were taken to a city bath. They were made to undress and undergo an inspection for venereal disease. Sam worried that he would be identified since he was circumcised. When it was his turn, Netzel, who was watching from across the room, told the doctor to be sure to inspect Sam carefully to make sure he wasn’t a Jew. The German doctor looked at Sam and asked him his name. When Sam responded it was Andreas, the doctor told Netzel, “Andreas is a Christian name. This boy is not a Jew.” Sam never knew if the doctor was aware of his circumcision and was trying to help him or he simply did not know about circumcision.

Sam eventually ran away from the factory, only to be found by police a few weeks later working on a farm. (It was illegal to run away from a job.) He spent six weeks in a brutal SS prison camp and was returned to the factory. Netzel was still there spreading rumors. So Sam ran away again. In the end he would run away from five work camps, endure harsh conditions with little food or privacy, and narrowly survive falling bombs when the Allies began to fly air raids over Germany.

Throughout the war, Sam thought he was the only surviving Jew in Europe. It was a lonely and troubling thought. Sam wondered if he should even continue being a Jew. Should he marry a Jewish woman and bring Jewish children into a world of intolerance and violent anti-Semitism? Meanwhile, he could tell no one of his identity. He couldn’t trust the friends or even girlfriends he spent time with at the work camps. Would these friends remain friends if they knew he was a Jew?

Sam never forgot Netzel. After the war was over, in 1948, Sam went back to the factory and tried to find him. He got a certificate from the factory showing he had worked there (and a copy appears in his book). But Netzel was sick the day Sam showed up.

“Why would you want to see Netzel again?” I asked Sam.

“To tell him I was Jewish and ask him what his motivation was,” Sam said.

But what was the motivation of any of the Nazis, I wondered as I talked to Sam. In all these years since the war, has he ever made sense of this tragedy?

“It’s difficult to make sense about the Jewish history,” Sam said. “The last thousand years they were living with persecution…they were chased out from England, they were chased out from France, they were chased out from Germany, they were chased out of Spain. There was a thousand years of persecution. There’s not only persecution but dislike. The Jews were disliked by the non Jews.”

As a young boy, Sam and his brother joined a Zionist organization in their hometown. They dreamed of one day emigrating to Palestine and living in a Jewish state. Even during the war, this was Sam’s goal. As it turned out, he never did emigrate to Palestine. He ended up going to a far different part of the globe. I’ll pick up on that part of the story in the next of this three-part post.