Maybe, just maybe we wouldn’t have hit the deer if I hadn’t showed my husband the cool old hotel where I sometimes stay in Santa Rosa. If not for that 2-minute detour on our way home we may not have collided with the buck a half-hour later at 70 mph on the freeway.

Maybe, just maybe we wouldn’t have hit the deer if I hadn’t showed my husband the cool old hotel where I sometimes stay in Santa Rosa. If not for that 2-minute detour on our way home we may not have collided with the buck a half-hour later at 70 mph on the freeway.

The deer came out of nowhere. We were talking one minute, in the quiet bubble of my husband’s sleek grey Subaru. Then suddenly we saw the deer’s head, topped by impressive antlers, off to one side of our windshield. Our eyes locked for a split second. What was he doing there in the fast lane of the freeway? He was probably thinking the same thing as us.

The impact was swift. A loud couple of thuds reverberated against the front and side of the car as the deer’s body smashed against us. My husband instinctively veered to the right and pulled over to the shoulder of the highway. Fortunately, no other cars were around us at 10 pm. that night.

The car was badly damaged. Later our insurance would pay $10,000 to repair it. The deer didn’t survive. A highway patrol officer who pulled over told us he was lying in the median. We were practically in tears. “If I hadn’t showed you the hotel…” I said. “Or if we hadn’t spent five minutes talking in the car before we left…” We had just killed a living, breathing being.

On the way home we asked the tow truck driver if he sees many accidents like this. Yes, he said. Deers are nocturnal. I felt like I had just woken up from a dream, sitting high up in the middle seat of the tow truck between my husband and the driver.

I asked the driver about himself, just to get my mind off the deer. “Where are you from?” He told me he was from Petaluma and had recently returned from a tour of duty in Iraq. “Thank you for your service,” my husband said. But the driver said nothing and kept talking. Living in the Bay Area was getting too expensive, he said. He planned to get a job as a guard at a correctional facility somewhere up north.

The driver didn’t have to, but he towed our car all the way home to Berkeley. “It’s a quiet night,” he said.

**

When I was a child, I had recurring dreams of entering the “deer cave” down the hill from our house. My brother and I had discovered that the deer had a sort of cave under a bunch of trees and bushes at the bottom of our property. The cave was always dark even when it was sunny and bright outside. You could tell the deer slept there by the matted circles of grass on the ground. I only looked in once and I was afraid to get near it again.

In my dream I would be playing in the yard and then get closer and closer to the cave. I would peer inside and all kinds of fearful things would be waiting for me. Not just deer, but other things I can’t now remember. I would wake up in a sweat. My fear wasn’t irrational. Once a deer had kicked my dog in the face and knocked two teeth out. I had a respect for these silent, mysterious creatures that roamed the hills.

**

Running into the deer south of Santa Rosa wasn’t the first time I’ve hit a deer. When I was 19 years old I was driving to my family’s house when a deer suddenly jumped out of the bushes on top of my car. He smashed the windshield, got stuck in the ski rack for a moment, twisting the metal, and then ran off into a neighbor’s yard. In a daze, I drove the next block home, tiny shards of glass speckling my face. When my mom came out to say hi, she gasped at the sight.

I had been returning from a pre-marital counseling session with my pastor and my soon-to-be husband. I have no recall of anything we talked about in that meeting or really any other meeting we had, but I’ll always remember the deer. I wondered if the deer had been OK. I was glad for the safety glass on my car. Every time I saw the twisted ski rack on top of the car I remembered the collision I had with something wild.

**

Some years ago a friend asked me if I had a spirit animal. I had never heard of this and didn’t even know what it meant, but I immediately responded: a deer. Maybe I am even a little like a deer. I tend to be quiet, an observer. I like to wander around hills. At night my brain is busy. I often remember my dreams and ruminate on them for days afterward.

Actually, my friend later explained, a spirit animal is more like a guide. I’ve thought about this a lot over the years. In every encounter, deer—seemingly benign and gentle—have jolted me awake in some way. That time on the highway with my husband renewed our thankfulness for life, even as we grieved for the deer. When I ran into the deer when I was 19 it created a bonding moment with my mom. I could have walked down the aisle with a face full of scars but I didn’t.

Even my current battle with the urban deer in my neighborhood gives me some sense of adventure. In May I started spraying a concoction of garlic, cayenne pepper, eggs and water on the agapantha flowers in my front yard. These plants are supposed to be deer repellent, but the hungry deer around here eat them anyway. As soon as fat buds form at the end of each long stalk each spring, the deer nibble them off. I haven’t seen them bloom into big purple flowers for at least five years.

This year I decided to fight back and the spray worked. I felt slightly bad I ruined these plants for the deer but I also felt a little excited each morning when I found the buds still intact. Now all of the agapanthas are in full, bountiful bloom.

I haven’t seen any deer in my neighborhood for a while but two nights ago my son saw three coyotes in our yard. That both intrigued and worried me. They must be following the deer who come down from the hills. I won’t let my little dog out at night anymore.

We think we live in a controlled, tame environment, but nature—wild, fighting to survive, beautiful and fearsome—is just outside our door. How we react to these messengers from another world can teach us a lot about ourselves.

“Aloha, it’s so great to meet you,” Regina said as I stepped off the runway in sunny Kona. Hawaii.

“Aloha, it’s so great to meet you,” Regina said as I stepped off the runway in sunny Kona. Hawaii.

Do you have a favorite time of day? Maybe it’s looking forward to that first sip of coffee in the morning. Maybe it’s listening to your favorite song or podcast on the way home from work.

Do you have a favorite time of day? Maybe it’s looking forward to that first sip of coffee in the morning. Maybe it’s listening to your favorite song or podcast on the way home from work. “Sometimes the truth depends on a walk around the lake” – Wallace Stevens

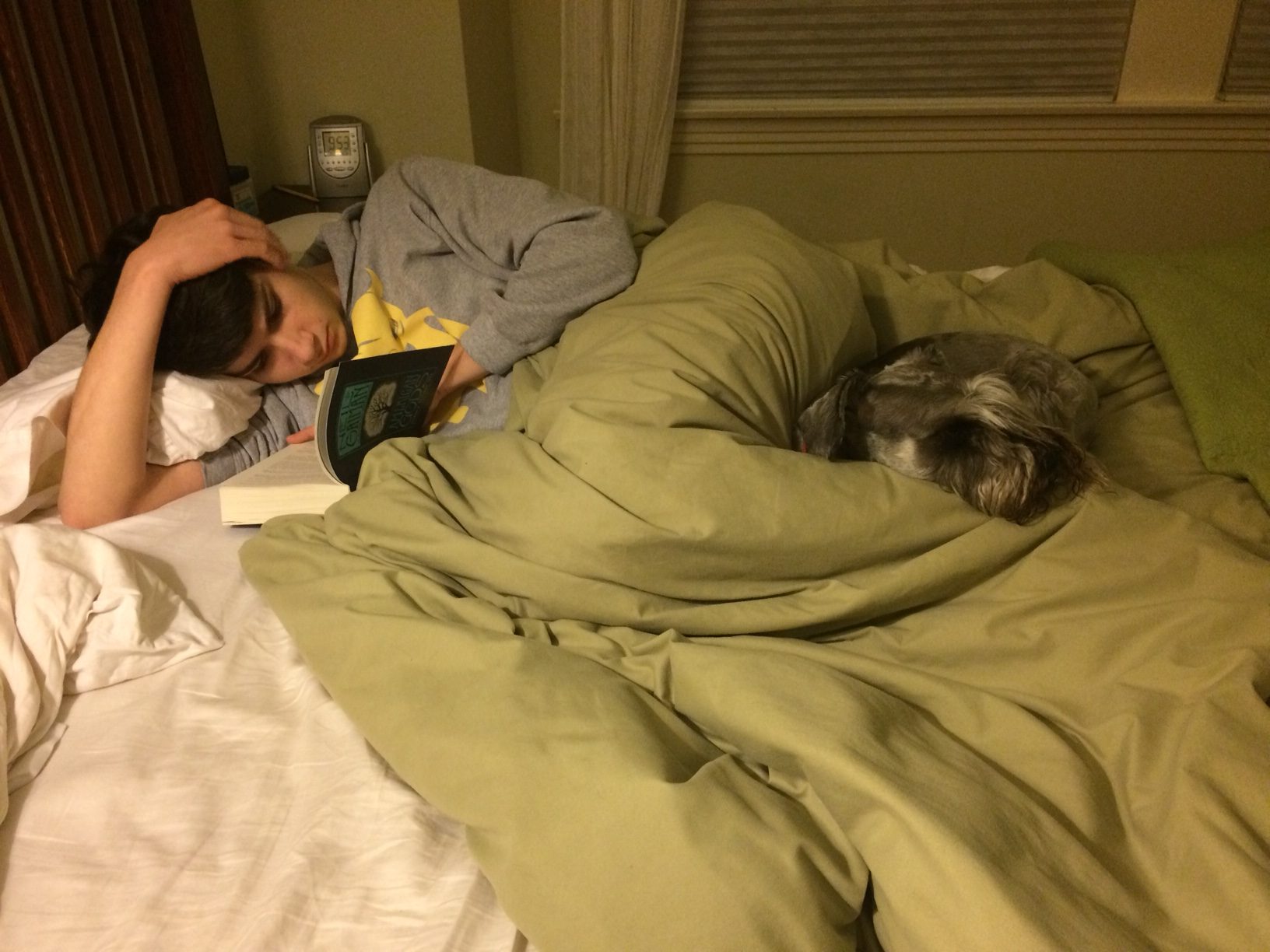

“Sometimes the truth depends on a walk around the lake” – Wallace Stevens My son and I surveyed the stacks of clean clothes on his bed. Did he have everything he needed for his second year in college? And what about his guitar propped against the wall? Should he bring that along too? We bantered back and forth about packing details and I tried to imagine what it was going to be like for my son to move into his first apartment off campus this year.

My son and I surveyed the stacks of clean clothes on his bed. Did he have everything he needed for his second year in college? And what about his guitar propped against the wall? Should he bring that along too? We bantered back and forth about packing details and I tried to imagine what it was going to be like for my son to move into his first apartment off campus this year.

As I explained in my last post, spending a week in the little town of Panyebar, Guatemala recently was a little like a family reunion. Our “family” of Mayan Partners supporters, ages 7 to 50+, joined a group of Guatemalans of all ages, and the results were lovely and heart-warming. Like any family though, there are complex dynamics at work and some situations feel so fluid and unresolved you can only let go and let God (hopefully) direct.

As I explained in my last post, spending a week in the little town of Panyebar, Guatemala recently was a little like a family reunion. Our “family” of Mayan Partners supporters, ages 7 to 50+, joined a group of Guatemalans of all ages, and the results were lovely and heart-warming. Like any family though, there are complex dynamics at work and some situations feel so fluid and unresolved you can only let go and let God (hopefully) direct.

Another situation that left me somewhat confused happened with a former employee of the school, a woman named Flory. Flory had been a secretary at the school until a few years ago when our group and local leaders decided to implement a policy to eliminate nepotism, which had caused some problems. (Flory is the daughter-in-law of the head of the local committee that runs the school. Her husband Feric and some other teachers also had to leave the school because of the nepotism rule.) Our group reached out to Flory after she lost her job and asked her to make handicrafts for sale in the U.S. as a way to earn income. For two years, she and a group of other women made Christmas ornaments that we sold. We sent many e-mails back and forth to coordinate. Then, this year, I stopped hearing from Flory. My many e-mails went unanswered. What had happened?

Another situation that left me somewhat confused happened with a former employee of the school, a woman named Flory. Flory had been a secretary at the school until a few years ago when our group and local leaders decided to implement a policy to eliminate nepotism, which had caused some problems. (Flory is the daughter-in-law of the head of the local committee that runs the school. Her husband Feric and some other teachers also had to leave the school because of the nepotism rule.) Our group reached out to Flory after she lost her job and asked her to make handicrafts for sale in the U.S. as a way to earn income. For two years, she and a group of other women made Christmas ornaments that we sold. We sent many e-mails back and forth to coordinate. Then, this year, I stopped hearing from Flory. My many e-mails went unanswered. What had happened?